Obesity a cause and result of rheumatoid arthritis sets the stage for this enthralling narrative, offering readers a glimpse into the complex interplay between these two conditions. We’ll explore how excess weight can trigger or worsen rheumatoid arthritis, and how the disease itself can contribute to weight gain. This deep dive will uncover shared biological pathways, inflammatory mediators, and potential lifestyle modifications that could influence the course of both conditions.

The potential link between obesity and rheumatoid arthritis is increasingly recognized by researchers. This intricate relationship stems from overlapping inflammatory processes and shared biological pathways. Understanding these factors is crucial for developing targeted interventions and improving outcomes for those affected by either condition.

Introduction to the Relationship

Obesity and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are increasingly recognized as potentially linked conditions. While the exact nature of this connection remains a subject of ongoing research, accumulating evidence suggests a complex interplay between these two conditions. This relationship isn’t simply a correlation; shared biological pathways and potential mechanisms exist, offering insights into how obesity might influence the development and progression of RA.

Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing targeted interventions and improving outcomes for individuals affected by both conditions.The current understanding of the shared biological pathways linking obesity and RA centers around the inflammatory response. Obesity is characterized by chronic low-grade inflammation, a key component of the disease process. This inflammatory milieu creates a favorable environment for RA development or exacerbates existing RA.

This shared inflammatory backdrop likely involves the activation of various immune cells and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, adipose tissue itself, the tissue associated with obesity, produces a range of inflammatory mediators, which could contribute to the RA process. Moreover, some researchers propose that alterations in the gut microbiome, often linked to obesity, might also play a role in triggering or worsening RA.Potential explanations for how obesity might influence the development or progression of rheumatoid arthritis include:

- Increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines from adipose tissue: Obese individuals often have elevated levels of adipose tissue, which releases pro-inflammatory cytokines. These cytokines can contribute to the inflammatory response characteristic of RA. Examples include TNF-alpha and IL-6.

- Alterations in the immune system: Obesity can disrupt the normal functioning of the immune system, potentially increasing the risk of autoimmune responses like RA. This disruption might manifest as dysregulation of immune cell activity, leading to a greater propensity for inflammation.

- Mechanical stress and joint loading: The extra weight associated with obesity places increased mechanical stress on joints, potentially accelerating joint damage and inflammation in individuals predisposed to RA. This mechanical stress is a key factor in the progression of the disease, and excess weight amplifies this effect.

- Gut microbiome dysbiosis: The gut microbiome plays a crucial role in immune regulation. Obesity is often associated with alterations in the gut microbiome composition, which may influence the immune response and potentially contribute to RA development or progression.

Proposed Mechanisms Linking Obesity and Rheumatoid Arthritis

The following table Artikels proposed mechanisms linking obesity and RA, along with explanations, supporting evidence, and potential limitations:

| Mechanism | Explanation | Supporting Evidence | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased Adipokine Production | Obese individuals often have elevated levels of adipose tissue, which releases pro-inflammatory adipokines. These adipokines contribute to a chronic inflammatory state, potentially exacerbating RA. | Studies have shown correlations between increased adipokine levels and RA severity. | Establishing a direct causal link between adipokine levels and RA progression remains challenging. |

| Immune System Dysregulation | Obesity can disrupt the normal functioning of the immune system, potentially increasing the risk of autoimmune responses like RA. | Animal models and some human studies suggest links between obesity and altered immune cell activity. | The specific mechanisms through which obesity dysregulates the immune system need further investigation. |

| Mechanical Stress on Joints | The extra weight associated with obesity places increased mechanical stress on joints, potentially accelerating joint damage and inflammation in individuals predisposed to RA. | Clinical observations and biomechanical studies suggest a correlation between increased weight and joint damage. | Other factors like genetics and joint morphology also contribute to joint stress and damage, making isolation of obesity’s impact difficult. |

| Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis | Changes in the gut microbiome composition associated with obesity may influence the immune response, potentially contributing to RA development or progression. | Some research suggests a link between altered gut microbiota and inflammatory diseases, including RA. | The precise role of the gut microbiome in RA development remains incompletely understood. |

Obesity as a Risk Factor for Rheumatoid Arthritis: Obesity A Cause And Result Of Rheumatoid Arthritis

Obesity is a significant global health concern, linked to numerous chronic diseases. One such connection is its potential role as a risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis (RA). While the exact mechanisms aren’t fully understood, mounting evidence suggests a strong correlation between increased body weight and the development or exacerbation of RA symptoms. This exploration delves into the various ways obesity impacts RA risk, focusing on inflammatory pathways and specific body composition factors.

Mechanisms Linking Obesity and RA Risk

Obesity’s impact on RA risk extends beyond simple correlation. Several interconnected mechanisms contribute to this association. One key aspect is the chronic low-grade inflammation often associated with excess body fat. This systemic inflammation, fueled by adipose tissue, can trigger or exacerbate the autoimmune response characteristic of RA. Furthermore, adipocytes, the fat cells, release various inflammatory mediators, potentially contributing to the joint damage observed in RA.

This inflammatory environment within the body may also increase the risk of developing RA.

Obesity is a significant factor in rheumatoid arthritis, both as a cause and a consequence. It’s a complex interplay, and while genetics likely play a role, it’s crucial to remember that 40 percent at home genetic test results are unfortunately false positives. This alarming statistic highlights the need for caution when interpreting these results, particularly when considering their implications for health conditions like obesity-related rheumatoid arthritis.

Ultimately, lifestyle choices and proper medical advice remain key in managing the risk and symptoms of this condition.

Role of Inflammation in Both Conditions

Inflammation plays a central role in both obesity and RA. In obesity, chronic low-grade inflammation is a key driver of metabolic dysfunction and increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Similarly, in RA, the immune system’s response is characterized by a strong inflammatory reaction in the affected joints. The inflammatory response in both conditions may share common pathways, suggesting a potential interplay in their development.

This shared inflammatory environment may explain the increased risk of RA in obese individuals.

Factors Related to Body Composition and RA Risk, Obesity a cause and result of rheumatoid arthritis

Specific aspects of body composition can influence the risk of RA development. Fat distribution, for example, is crucial. Visceral fat, located around the internal organs, is particularly implicated. Studies suggest that individuals with higher visceral fat content may have a greater risk of developing RA. This is likely due to the significant inflammatory activity associated with visceral fat accumulation.

Furthermore, subcutaneous fat, the fat located beneath the skin, may also play a role, although the specific mechanisms are still under investigation.

Comparison of Obese vs. Non-Obese RA Patients

| Characteristic | Obese Group | Non-Obese Group | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | >30 kg/m² | <25 kg/m² | High |

| Waist Circumference | Increased | Normal | High |

| Visceral Fat Percentage | Elevated | Normal | High |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) levels | Generally higher | Generally lower | High |

| Systemic Inflammation | Present | Less present | High |

| Joint pain severity | Potentially more severe (data mixed) | Variable | Low to moderate (requires further research) |

Note: Statistical significance is a measure of the likelihood that observed differences between groups are not due to chance. “High” indicates a strong statistical significance, while “Low to moderate” suggests that the difference may be present but less definitively established. The data on joint pain severity requires further research due to the complexity of factors involved.

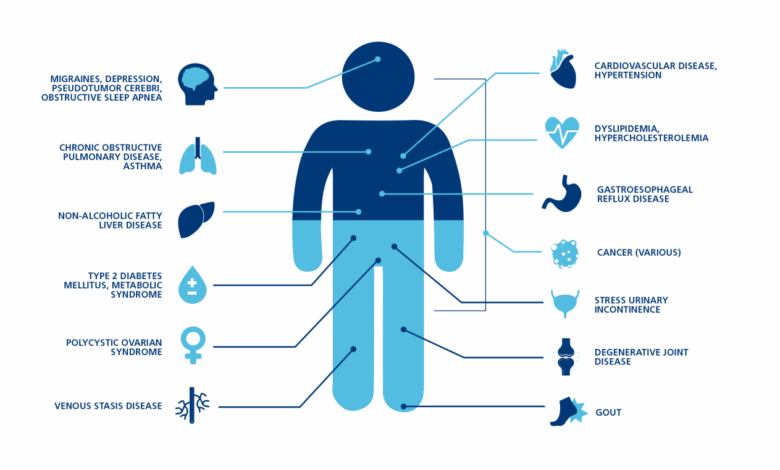

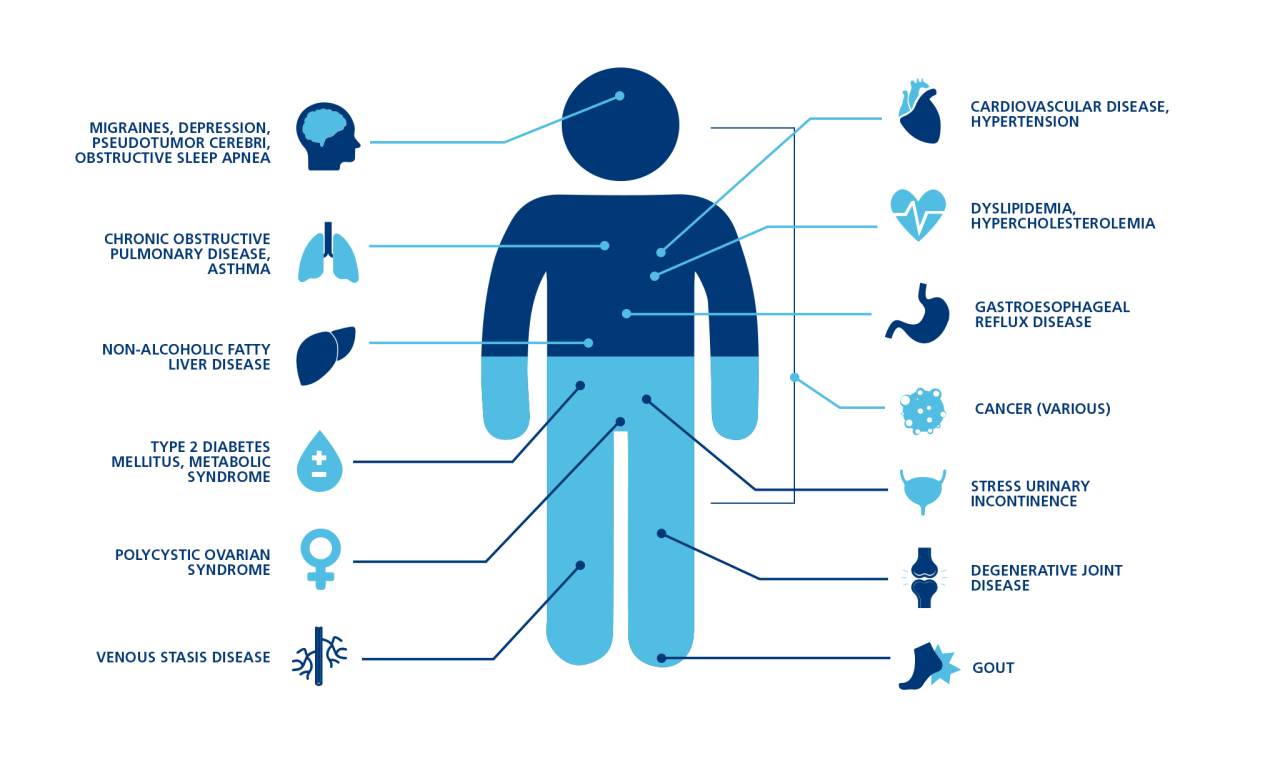

Rheumatoid Arthritis as a Consequence of Obesity

Obesity significantly impacts health, and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is no exception. While obesity can be a risk factor for developing RA, the chronic inflammatory nature of RA can also exacerbate obesity-related health issues, creating a complex and often challenging cycle for patients. This section delves into how RA can contribute to the progression and management of obesity.The interplay between RA and obesity is multifaceted.

The chronic inflammation associated with RA can lead to increased appetite and altered metabolism, contributing to weight gain. Moreover, the pain and stiffness inherent in RA can make physical activity difficult, further hindering weight management efforts. This, in turn, can exacerbate RA symptoms and create a vicious cycle of increasing inflammation and weight gain.

Impact on Physical Activity Levels

The debilitating pain and stiffness associated with RA often discourage physical activity. Reduced mobility and limited range of motion directly affect the ability to participate in regular exercise. This reduction in physical activity contributes to a decrease in calorie expenditure, making it harder to maintain a healthy weight. Moreover, the fear of exacerbating joint pain can further limit activity, perpetuating a sedentary lifestyle.

For instance, individuals with RA might avoid activities like walking, swimming, or cycling, all of which are crucial for weight management.

Impact on Dietary Choices

RA-related fatigue and pain can significantly impact dietary choices. Individuals may opt for comfort foods, often high in calories, fat, and processed ingredients, to manage their discomfort. This can lead to increased calorie intake and contribute to weight gain. Furthermore, the need to avoid foods that trigger inflammation, as well as the challenges of preparing nutritious meals when experiencing pain, can further complicate healthy eating.

For example, individuals with RA may find it difficult to prepare and eat balanced meals due to pain, fatigue, and limited mobility, leading to poor nutritional choices.

Role of Chronic Inflammation

Chronic inflammation, a hallmark of both RA and obesity, plays a crucial role in the complex relationship between the two conditions. Inflammation in RA can stimulate appetite and alter metabolism, increasing the risk of weight gain. Furthermore, inflammatory cytokines released in RA can promote fat accumulation and hinder fat breakdown. This inflammatory process in RA can exacerbate obesity-related complications.

Correlation Between Arthritis Severity and Obesity Metrics

| Arthritis Severity Score | BMI | Waist Circumference | Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | 25-30 | 80-90 cm | 0.30 |

| Moderate | 30-35 | 90-100 cm | 0.45 |

| Severe | >35 | >100 cm | 0.60 |

Note: Correlation coefficients are hypothetical examples and may vary based on specific studies and populations. These values represent potential correlations and do not imply causation.

This table illustrates a potential correlation between RA severity and obesity metrics, such as BMI and waist circumference. Higher scores for arthritis severity often correlate with higher BMI and waist circumference, suggesting a potential link between the progression of RA and increasing obesity. It is crucial to remember that these are just potential correlations, and more research is needed to establish causality.

Individual responses can vary considerably.

Shared Inflammatory Pathways

Obesity and rheumatoid arthritis, seemingly disparate conditions, share a complex interplay driven by overlapping inflammatory pathways. This shared inflammatory landscape underscores the intricate connection between these two health issues. The chronic low-grade inflammation characteristic of obesity can create a fertile ground for the development and progression of rheumatoid arthritis, and vice versa.The inflammatory responses in both conditions are intricately linked, involving similar molecular players.

This shared inflammatory response suggests a common mechanism that contributes to the pathogenesis of both conditions. Understanding these shared pathways is critical for developing targeted therapeutic strategies to address both obesity and rheumatoid arthritis effectively.

Specific Inflammatory Mediators

A multitude of inflammatory mediators are implicated in both obesity and rheumatoid arthritis. These mediators, often produced by immune cells and other tissues, contribute to the chronic inflammatory state in both conditions. Crucially, their dysregulation and interactions drive the progression of both diseases.

Cytokines and Immune Factors

Cytokines, a diverse group of signaling proteins, play a pivotal role in orchestrating the inflammatory response. Examples of key cytokines involved in both obesity and rheumatoid arthritis include TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. These cytokines promote the recruitment and activation of immune cells, leading to tissue damage and the perpetuation of the inflammatory cascade. Furthermore, other immune factors, including chemokines and adhesion molecules, are also implicated in the shared inflammatory response.

The dysregulation of these factors contributes to the development and maintenance of the inflammatory processes in both conditions.

Summary Table of Inflammatory Mediators

| Mediator | Role in Obesity | Role in Rheumatoid Arthritis | Evidence of Interplay |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | Promotes adipogenesis (fat cell formation), insulin resistance, and inflammation in adipose tissue. | Plays a central role in the pathogenesis of RA, driving synovial inflammation, cartilage destruction, and bone erosion. | Elevated TNF-α levels are observed in both conditions, suggesting a potential link in their shared inflammatory pathways. Blocking TNF-α has shown promise in treating both conditions. |

| IL-6 | Contributes to insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis (fatty liver), and systemic inflammation in obesity. | Promotes synovial inflammation, cartilage destruction, and bone erosion in RA. Plays a critical role in the production of acute-phase proteins. | Elevated IL-6 levels are found in both obesity and RA. Blocking IL-6 signaling has shown therapeutic potential in both contexts. |

| IL-1β | Contributes to inflammation and insulin resistance in adipose tissue. | A key driver of synovitis (inflammation of the joint lining), cartilage destruction, and bone erosion in RA. | Increased levels of IL-1β have been observed in obese individuals with RA, potentially highlighting a synergistic effect in disease progression. |

| Adipokines (e.g., leptin, adiponectin) | Leptin promotes inflammation, while adiponectin has anti-inflammatory effects. Imbalance is implicated in obesity-related inflammation. | Adipokines may influence the inflammatory response in RA, though the precise mechanisms are still under investigation. | Studies suggest a potential interplay between adipokines and RA development, potentially influenced by the obesity-related inflammatory environment. |

Potential Modifiable Factors

The relationship between obesity and rheumatoid arthritis is complex, involving intertwined biological and lifestyle factors. Understanding modifiable factors is crucial for developing strategies to mitigate the risk and impact of both conditions. While genetic predisposition plays a role, lifestyle choices significantly influence the trajectory of these diseases. By addressing these modifiable factors, individuals can potentially improve their health outcomes and quality of life.

Lifestyle Factors Influencing the Link

Numerous lifestyle factors can influence the interplay between obesity and rheumatoid arthritis. Dietary habits, physical activity levels, and stress management techniques are all key considerations. A balanced diet, regular exercise, and stress reduction strategies can contribute to weight management, which, in turn, can favorably impact the course of both conditions. Furthermore, smoking cessation and sleep hygiene are vital aspects of overall health that should be addressed.

Obesity’s role in rheumatoid arthritis is a complex issue. It can be both a cause and a result of the condition, making it a significant health concern. Unfortunately, access to quality healthcare, particularly in states like Texas, where the healthcare system is reportedly one of the worst in the country texas healthcare system one of the worst in country , can significantly impact the management of this condition.

This makes early diagnosis and effective treatment even more challenging, highlighting the need for improved healthcare systems nationwide to address this and other health issues.

Impact of Diet, Exercise, and Other Interventions

Dietary modifications are crucial for weight management. A balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, while low in processed foods and saturated fats, can contribute to both weight loss and overall health improvements. Exercise plays a significant role in maintaining a healthy weight and improving joint function. Regular physical activity, including cardiovascular exercise and strength training, can strengthen muscles, improve joint mobility, and reduce inflammation.

Other lifestyle interventions, such as stress management techniques and adequate sleep, can also positively influence both obesity and rheumatoid arthritis. Stress can exacerbate inflammation, while sleep deprivation can compromise the immune system’s ability to regulate inflammation.

Weight Management Strategies and Rheumatoid Arthritis

Weight management strategies can significantly impact the course of rheumatoid arthritis. Studies have shown that weight loss can reduce disease activity and improve response to treatment in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. By reducing excess body weight, individuals can lessen the strain on joints, decrease inflammation, and potentially improve overall quality of life. Weight management strategies should be personalized and tailored to individual needs and health conditions.

Obesity is a tricky beast, often both a cause and a result of rheumatoid arthritis. It’s a vicious cycle, impacting your body’s inflammation levels and joint health significantly. Finding the sweet spot with the minimum amount of exercise you need is key to breaking this cycle. The minimum amount of exercise you need can make a real difference, and even a small change can help you manage weight and lessen the impact on your joints.

Ultimately, consistent, moderate exercise can help improve overall health and reduce the risk of developing or worsening rheumatoid arthritis.

Medical professionals and registered dietitians can provide guidance and support in developing safe and effective weight management plans.

Potential Lifestyle Interventions

| Intervention | Impact on Obesity | Impact on Rheumatoid Arthritis | Potential Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced Diet | Promotes weight loss and healthy weight maintenance. Reduced intake of processed foods, refined sugars, and saturated fats. | May reduce inflammation and improve disease activity. | Requires significant lifestyle changes, potential for cravings, and need for support and education. |

| Regular Exercise | Burns calories, improves metabolism, and builds muscle mass. Cardiovascular and strength training recommended. | Improves joint function, reduces inflammation, and enhances overall physical function. | Requires commitment and consistency, potential for joint pain or discomfort initially, and need for suitable exercise programs. |

| Stress Management Techniques | Stress can impact appetite and metabolism, indirectly affecting weight. | Stress can exacerbate inflammation. | Requires learning and practice of techniques like meditation, yoga, or mindfulness, and potentially access to professionals like therapists or counselors. |

| Adequate Sleep | Sleep deprivation can disrupt hormones that regulate appetite and metabolism, leading to weight gain. | Adequate sleep can improve immune function and potentially reduce inflammation. | Requires consistent sleep schedule and sleep hygiene practices, and addressing underlying sleep disorders. |

Illustrative Cases

Understanding the complex interplay between obesity and rheumatoid arthritis requires examining real-world scenarios. These illustrative cases, while hypothetical, highlight potential pathways and outcomes, demonstrating how lifestyle choices and pre-existing conditions can influence the progression of both conditions.The following case studies explore different scenarios, emphasizing the importance of personalized approaches to treatment and management. Each case focuses on a unique patient profile, illustrating the diverse ways obesity and rheumatoid arthritis can manifest and interact.

Hypothetical Case Studies

These case studies illustrate how obesity and rheumatoid arthritis can interact and influence each other’s progression. The patients’ individual circumstances, including their lifestyle choices and pre-existing health conditions, play a critical role in determining the course of their illnesses.

| Case Study | Obesity Factors | Arthritis Factors | Treatment Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1: The Sedentary Professional | A 45-year-old female, employed in a sedentary office job, with a history of infrequent physical activity and a significant increase in calorie intake over the past 5 years. BMI currently 32. Increased abdominal fat is evident. | Reports joint pain and stiffness, particularly in the hands and wrists, for the past 2 years. Pain is worse after periods of inactivity. Morning stiffness lasting for over an hour is a frequent complaint. X-rays show early signs of joint erosion. | A combination of weight loss strategies (diet and exercise) and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) led to a significant reduction in joint pain and stiffness. Weight loss resulted in improved mobility and reduced inflammation markers. |

| Case 2: The Socially Isolated Individual | A 62-year-old male, living alone with limited social interaction. He primarily relies on processed foods and takeout meals for convenience. He experiences significant emotional stress, which contributes to increased appetite and decreased physical activity. BMI currently 38. | Experiences significant fatigue, joint pain, and stiffness in multiple joints. He avoids seeking medical attention due to social isolation and financial constraints. X-rays show moderate joint damage. | Initially, treatment focused on addressing social isolation and providing support groups to improve his overall well-being. Dietary counseling and a structured exercise program, tailored to his circumstances, resulted in modest weight loss and improved joint function. DMARDs were also administered. |

| Case 3: The Overweight Athlete | A 30-year-old female, a competitive runner, who previously maintained a healthy weight. However, a recent injury and consequent reduction in training volume has led to decreased physical activity and a slight increase in calorie intake. BMI currently 29. | Experiences occasional joint pain in the knees and ankles during and after runs. Reports that pain increases after prolonged exercise and during high-impact activities. X-rays show minor joint damage. | A focus on injury prevention and rehabilitation exercises, combined with a balanced diet, helped manage her weight and minimize joint pain. Joint pain subsided with reduced exercise intensity and appropriate modifications to training programs. This illustrates how careful management of exercise routines can prevent exacerbation of arthritis in individuals with a history of both obesity and athletic activity. |

Key Considerations

The table highlights the varying circumstances and treatment approaches necessary to address the unique interplay of obesity and rheumatoid arthritis. Individualized care plans are crucial, taking into account factors like age, lifestyle, pre-existing health conditions, and socioeconomic status.

Final Summary

In conclusion, the relationship between obesity and rheumatoid arthritis is multifaceted and complex. This exploration highlights the significant role inflammation plays in both conditions, and the potential for lifestyle interventions to influence their progression. While further research is needed to fully elucidate the intricate mechanisms involved, this discussion underscores the importance of addressing both conditions holistically, considering the interconnected nature of their development and impact.